I have an old, worn, slightly rumpled sign in the front of my classroom that simply says “Yet.” I believe in the transformative power of the word. “Can’t” and “never” are a big part of my students’ lexicons, and I spend many moments steering their thoughts towards “yet.”

Let’s dive in:

Student: “I can’t do this stupid work.”

Me: “You can’t do it yet.”

Student: “Why do we even need to do this?”

Me: (Ignoring the myriad of responses about how systems thinking and procedural learning help develop their still mushy frontal lobes) “Do you have soccer tonight?”

Student: “Yes, we have a tournament coming up.”

Me: “Exactly” (Walks away.)

Keep in mind that I do not walk away to instigate or frustrate. Rather, I take a few steps to give them a moment to think. Returning a moment later, I always ask, “Why bother going to practice?”

A new discussion begins about what skills they are working on, how often they practice, and what their athletic goals may be for the future. It really does not make a difference if this student plays a sport, video games, is in a band, sings, dances, etc. What matters is the opportunity to remind them that they work hard in other aspects —hours and hours, if not days and weeks of their lives, are spent practicing for what is, by all realistic measures, a very short demonstration of those skills.

How is that practice any different than notes, reading, labs, discussions, inquiry activities, fieldwork, clubs, concerts, or other performances? The disconnect is often sizeable. Outside of school, life is not the same as inside the walls of a classroom. I will be the first to admit that the carbon cycle is not nearly as fun as hitting that one note during your choir solo (come on—you know THE note that I am referring to), but the preparation to be successful is the same. As a coach, a 100-meter sprinter may spend practice getting into and out of the starting blocks, over and over, as we measure knee angles and arm and hand positions and talk out the phases in an effective sprint. Hours and hours are spent to arrive in the moment when it all has to come together—for about 12 seconds. The practice-to-performance ratio is skewed heavily in the corner of practice.

To learn what to do when it is time to perform, we have to practice. The medium may be different, but the prep and possible outcomes are fundamentally the same. Energy leads to action, and action leads to performance when it matters.

I then usually ask what the difference is between “good” and “great.” This often leads to numerous answers, but it almost always distills down to working at a skill. “Why does your coach have taking hundreds of shots on goal? “Or “I see you out on the field after practice, taking shots, fielding ground balls, going over that chorus just one more time.”

They know that:

No expert was not once a beginner. Reminding students that this struggle is not different from learning how to throw that perfect curveball or hitting their mark during the drumline show is paramount. This task, even though it is difficult now, has the ability to change your trajectory.

It is important to note that teachers must frame the journey through productive struggle. Authentic tasks, supports, scaffolding, other methods of differentiation are key.

The shift towards a student mindset has definitely come to the forefront of education in the past decade. Not that we had ignored it, per se, but more that it was assumed that engaging in curriculum was indicative of a growth mindset. Instead, there are some sneaky side effects to our focus on fostering growth mindsets. Rigid and negative thinkers often will see productive struggle as fixed, meaning that a “fail” or a “loss” is permanent. This can become cumulative when a student perceives themselves as “failing at growth mindset.” That self-fulfilling prophecy can actually have the effect of increasing a fixed mindset, making school more difficult as they attempt to get past not achieving a growth mindset.

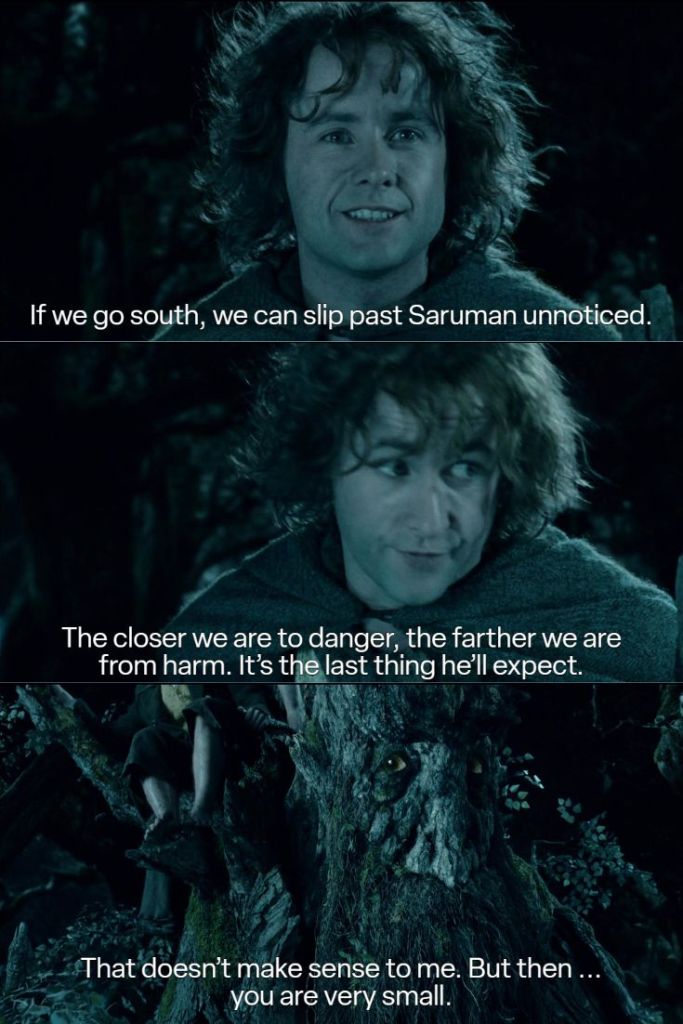

So, I try to reframe the development of a growth mindset through developing resilience and productive struggle. The idea that the struggle is the journey, and all journeys (cue the Lord of the Rings soundtrack here) have challenges and difficulties. My middle son plays Dungeons and Dragons, and hearing the tales of campaigns fraught with dangers makes the journey all the more exciting. So, my focus is on solving the problem. How many ways can we think of to tackle this task? And, like the road to Mt. Doom, it is expected to be scary, bumpy, and dangerous. Once students see that they CAN work through tasks, even when they fail along the way, the end result is not an all or nothing proposition.

Another way of thinking about productive struggle is focusing on students’ thinking as malleable. Struggle towards constant growth can serve to help students in all aspects of learning. Seventh graders taught that intelligence is malleable showed significant improvements in math grades, illustrating the transformative power of adopting a growth mindset in educational settings.

Students show this type of thinking outside of the classroom all of the time. For example, how often have you seen a child struggle through a video game, reaching the point of rage-quitting, and then returning after a cooldown period to try again? The mindset is there, and they will utilize it. My biggest goal is to create curriculum that engages that type of thinking. I would love to know more about how you engage students of all “thinking types.” What strategies have become “best practices” in your classroom, on your team, or in your club?